When we started designing our small lake house (an ADU) here in Maine, we quickly ran into an important constraint: impervious surface limits. Our town allows a maximum of 15% impervious surface lot coverage and after doing our survey, we found that we were sitting at 14%.

Suddenly, we had to become fluent in a whole new language: impervious, pervious, vegetated, non-vegetated, and what all of that means for design.

Impervious vs. Pervious Surface

What’s an Impervious Surface?

An impervious surface is anything that water can’t soak through. Instead of infiltrating the soil, rainwater runs off, which can lead to erosion, flooding and pollution if not managed properly.

The rain hits an asphalt driveway and runs off, vs. rain that soaks into a grassy lawn.

Common examples of impervious surfaces include: Asphalt or concrete driveways, roofs, solid patios and decks, walkways and compacted gravel (yes, even that!)

What’s Considered Pervious or Vegetated?

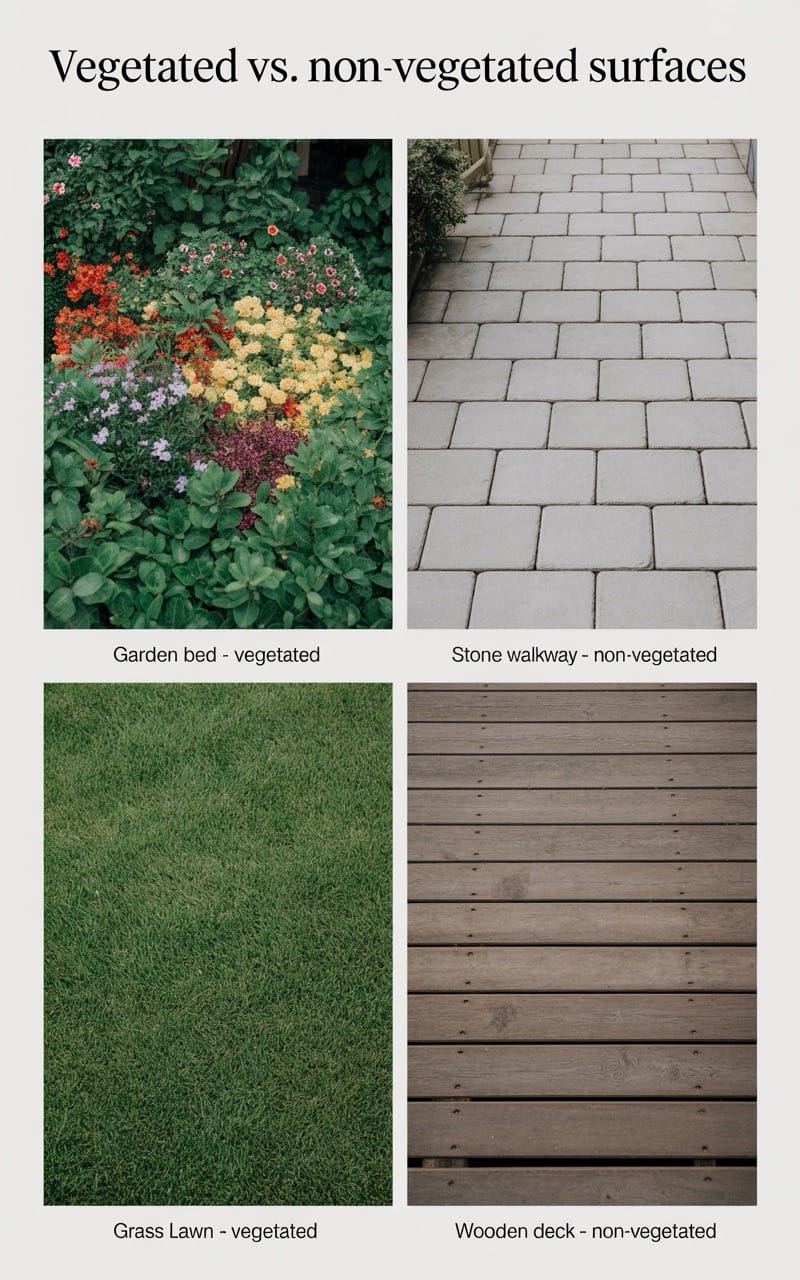

Our town doesn’t just talk about impervious vs. pervious/permeable – they also classify surfaces as vegetated or non-vegetated. They strongly prefer vegetated, meaning green and plant-covered, not just technically permeable.

Here we show the difference between vegetated and non-vegetated. In our town, only 15% of our lot can be non-vegetated.

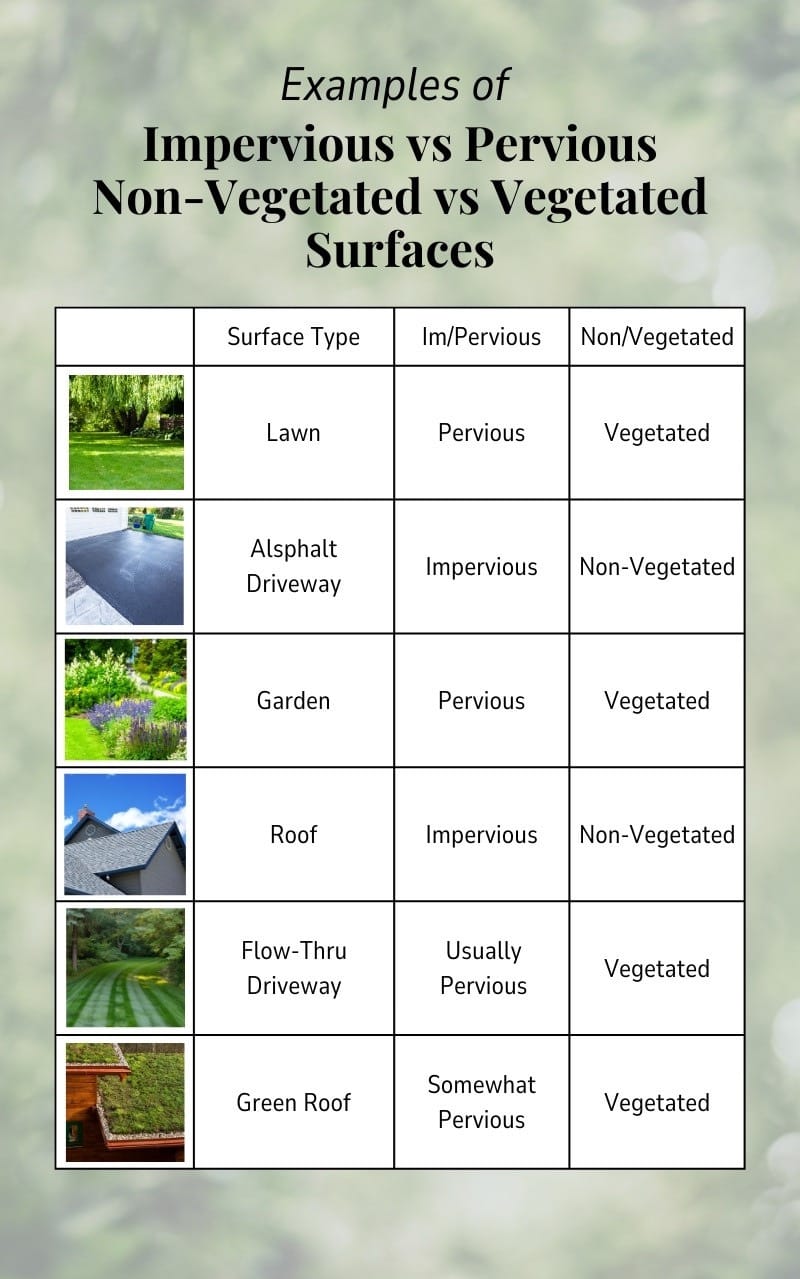

More details on impervious vs. pervious and non-vegetated and vegetated.

Ideas for Permeable and Vegetated Design

We’re trying to come up with creative ways to reduce our current impermeable or non-vegetated lot coverage. Here are a few ideas that we’re exploring:

Permeable Driveway Ideas

The biggest impervious challenge for us is our very long asphalt driveway. It’s due for repair, which makes this the perfect time to go greener.

We’re planning to remove unnecessary asphalt. For example, we can easily eliminate 320 sq. ft. of asphalt near our current cottage entrance and replace it with vegetated surface – gaining that space back for the ADU’s footprint. Other ideas include:

Looking at a ‘flow-through’ driveway: This would be actual grass grown over a compacted base. We’re hoping this might count as vegetated in our town.

Two-tread design: Two narrow strips (concrete, pavers or gravel) under the tires, with grass in between.

Grid-style pavers: Concrete or stone pavers with open joints where clover or grass grows. A great way to keep things functional but green. This is not allowed in our town but might be in others.

Permeable Patio Designs

When our ADU is complete, we’ll want a patio but we’ll need to be strategic. A traditional concrete patio? Major impervious penalty.

Our plan: repurpose existing flat rocks from our property to create a natural stone patio, mixing in ground covers or moss to keep it usable and vegetated.

Permeable Walkway Inspiration

Walkways are another opportunity to soften your impervious surface coverage.

We’re leaning toward flagstone stepping paths with moss or thyme in between – no gravel, just texture, plantings and flow.

Sustainable Landscaping with Natural Materials

Instead of a sprawling lawn or bark mulch, we’ll be incorporating native plants, wildflower borders, blueberry and blackberry plantings, natural boulders and rock accents.

These choices are beautiful, low-maintenance, and minimize runoff — all while helping us stay under our impervious limit.

A Few More Creative Solutions (May Vary by Town)

These ideas may not work everywhere, but might be allowed in more flexible zoning areas:

Pavers with grass in between.

Reclassify hard surfaces – Use permeable pavers with vegetation in between and an entire set up below to encourage infiltration.

Add vegetated swales or rain gardens – These planted depressions catch and absorb stormwater runoff.

Consider a green roof (even small ones) – Some towns may allow green roofs to count as partly vegetated.

Other Micro-Adjustments

- Remove gravel paths and replace with ground cover + stepping stones

- Replace hard edging with soft, planted borders

- Ask about spaced-deck boards over soil

- Sketch out rain garden zones to manage runoff

Final Thoughts

If you’re building in Maine, or anywhere with environmental zoning, don’t wait to learn about impervious surface limits. Rules can be strict, and early planning can save major design headaches. The good news? With some creative and eco-conscious design choices, you can meet code and create a landscape that’s functional, beautiful, and better for the planet.